The typesetter (Ips typographus) and dead wood

As a graphic designer, I spent 47 years in the graphic arts profession, and at the Graphic School Eindhoven in 1972, to learn and understand the basics of the graphic arts, you were taught the subject of typesetting. Hence the ‘typesetter’ intrigues me as a former graphic designer.

In a typesetting hook, I set lead typeface, numbers, characters and spaces into lines of text from left to right in mirror writing. I extracted these from drawers that were slid into a typesetting pen. Each drawer had its own font and ornaments and was divided into an upper compartment (for uppercase letters), a lower compartment (for lowercase letters) and a section for special characters like exclamation mark, percentage signs, etc. A total of 152 boxes. When the lines of text or blocks were set, I would tie them all around using string and this is how I made up book pages, which were printed in a printing press. A page consisted of thousands of characters and pieces of white.

I remember standing with my back to the letter cupboard during distribution and throwing the lead letters back into the drawers over my shoulder, with the result that the next pupil found the letters and characters in the wrong place in the cupboard. Annoying of course but we did not see the point of typesetting, after all, there were already typesetters doing this pointless work. But, said the typesetting teacher, ‘if the electricity goes out, the paper has to be printed anyway’ so typesetting was the way to go. In retrospect, a strange argument because printing presses were also connected to the electricity grid, weren't they?

The worst part was distributing after printing to put all the letters and characters back in the right drawers and boxes so that when making new texts, everything was in the right boxes.

I remember standing with my back to the letter cupboard during distribution and throwing the lead letters back into the drawers over my shoulder, with the result that the next pupil found the letters and characters in the wrong place in the cupboard. Annoying of course but we did not see the point of typesetting, after all, there were already typesetters doing this pointless work. But, said the typesetting teacher, ‘if the electricity goes out, the paper has to be printed anyway’ so typesetting was the way to go. In retrospect, a strange argument because printing presses were also connected to the electricity grid, weren't they?

The inventor of typesetting

The German printer and goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1400-1468) invented typesetting with loose lead letters around 1450. Before that, the writing of bibles and books was done by monks and hence the expression ‘monks’ work’ which indicated that writing bibles and books was a huge job. His best-known work is the Gutenberg Bible, completed in 1455.

The last mile weighs the hardest

This means that finishing a task or assignment is the hardest; that last bit requires the most perseverance to literally put the last ‘piece of lead’ here because it became heavy to hold the setting hook. So the saying could then have its origins in the printing profession.

But what is the typesetter and how does he set his letters

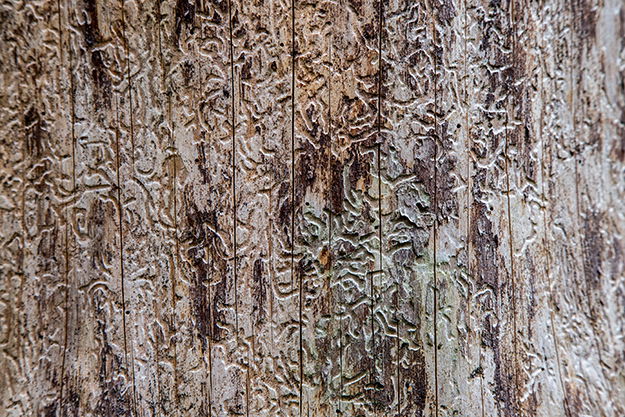

It wasn't until my visit to the Chapel of the Holy Guardian Angel that I first heard of the typesetter as an insect. Coos van Wageningen told me that this little beetle is also responsible for tree mortality in the Molenbosch. The Letterzetter Ips typographus is a 4.0 - 5.5 mm long, shiny reddish-brown to black beetle with cover shields that are heavily dented at the end. It particularly likes spruce, such as Norway spruce (Christmas tree) and Douglas fir. Larch trees are not safe from this beetle either, and there can be thousands of these beetles in a tree. In spring, around April, the male beetle drills a passage under the bark of the trunk of felled, weakened or dying trees and builds a ‘mating chamber’ or passage about ten centimetres long. It then secretes a chemical to attract females. And the female lays eggs in this passage. The white larvae, born in the mating chamber, eat new corridors from the main corridor, forming patterns resembling letters. The thousands of beetles dig tunnels in the tree, damaging the layer with which the tree makes new wood. As a result, the tree eventually dies.

Trees perish due to letter beetle

Parts of the forest areas De Paltz and the Monnickenbos (how appropriately monk's work and the writing of bibles and books) in Soest have been felled by the lightning-fast advancing beetle. The Soest municipality thus tackled the spread of the typesetter because this beetle species attacks trees that die as a result. In recent years, the typesetter caused massive damage to spruce trees in the German Harz Mountains. 80 to 90 per cent of the ‘breeding trees’ there have been eaten en masse by the ruthless beetle, according to the Niedersächsische Landesforsten. After World War II, only young spruce trees were planted here at once as a result of the huge demand for timber to rebuild the country. The advantage is that spruce grows fast and the wood is very suitable as a building material.‘’

The plague

The wood-eating insect is plaguing forestry across Europe. Between 1950 and 2000, the bark beetle damaged 2.9 million cubic metres of wood per year on the continent. With increasing storms and persistent drought, the beetle will continue to plague European forests, a biologist from Bavaria said in a 2019 report.

What stops the bark beetle

The resin of a healthy tree and a wetter forest can stop insects. The tiny beetle seeks out a tree that has been damaged by a storm, for example, but because trees have suffered long periods of drought in spring and summer in recent years, the letter setter has free rein. The only way to combat the bark beetle is to fell trees and create a healthier, more diverse forest with a mix of tree species and ages. The monoculture of trees in a forest is a comfortable breeding ground for the typesetter.

Arnie Della Rosa